Tracking tigers through photographic capture has fast become the standard method through which a given population can be estimated. A tiger’s whereabouts, often wide-ranging and almost always shrouded in an immemorial air of magical mystery is difficult to confirm without the able assistance of such technology. Estimates of tiger populations for a specified area can help better plan conservation measures in conjunction with the local community and the State Forest Department. India is home to more than three-quarters of the global tiger population; reporting upwards of 2900 tigers. To generate this data, India conducts the world’s largest camera-trapping exercise—the All-India Tiger Estimation (AITE)—every four years to determine the number of tigers roaming its forests. These surveys are indispensable for tracking tiger population trends, documenting encouraging stories of success, while also bringing to our collective attention areas where populations are declining.

Camera-trapping evolved from the counting of tiger pugmarks. This earlier method of counting proved inaccurate and the installation of trigger-sensitive camera traps, or the application of ‘automatic photography’—perhaps first tested and thereafter inspired by F.W. Champion—led to the standardisation of its use in estimating and monitoring the population of a given species. Serving as a critical technical partner to the Forest Department in various states, WWF India helps build the capacity of officials on the procedure for camera-trapping; especially for the AITE by following the protocol advised by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

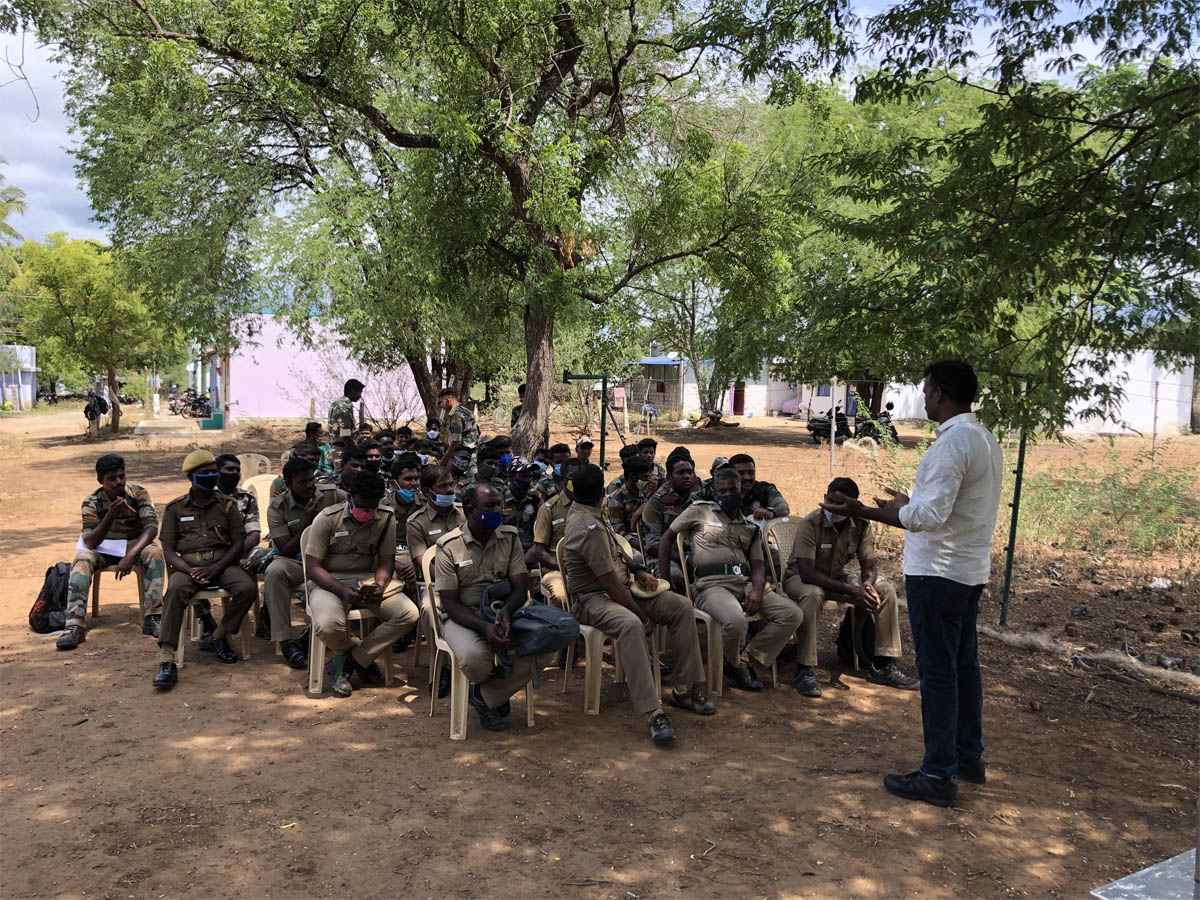

Recently, while on a visit to Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve (STR), I attended a training workshop on camera-trapping. This was targeted at forest officials—nearly 40 in number—from the surrounding ranges and divisions in STR in preparation for Phase IV of the AITE. The workshop was led by Mr. Krishna Kumar; WWF India’s tiger biologist from the Western-Ghats Nilgiris Landscape.

Sathyamangalam is—apart from its rich wildlife and habitat—infamously known as the then-haunt of the brigand Veerappan, who would live in the shadows of the forest. In his time, Veerappan was attributed to have killed upwards of 2000 elephants, numerous villagers and—even though this may be conjecture—tigers as well. Tigers were said to have all but vanished from STR at that point of time. Veerappan was killed by the authorities in 2004, and in 2005, the distinct impression of a tiger pugmark indicated the possible return of the predator to STR. In 2008, the WWF team directly sighted a tiger in Moyar Valley. In 2011, in a camera-trap study conducted by the State Government with support from WWF India, 28 individual tigers were photo-captured. Presently, as per the last AITE exercise, STR’s tiger population stands at 83, inclusive of adults and sub-adults. Please note that the breadth of area coverage surveyed in 2011, and subsequently in 2018 is very different, so drawing absolute numerical comparisons between tiger populations then and now is neither entirely constructive nor useful.

For successful execution of this Phase IV exercise, a total of 370 cameras will be deployed across pre-selected equally-apportioned and clearly demarcated grids in STR in accordance with NTCA protocol. Cameras are to be placed at knee-height, and tied to a tree/ pole with no obstruction in front of it. Two cameras are typically kept facing each other on opposite trees/ poles so as to capture both flanks of a moving tiger. The stripes of a tiger are as unique as a human fingerprint and these patterns can help identify each tiger individually. During the workshop, officials tied each camera around a tree, and tested its operation by crawling on the ground on all-fours; mimicking the movement and proportions of a tiger.

Prior to setting up these camera-traps, teams will first reconnoitre ‘beats’ (administrative units of the forest department that are predefined in their dimensions and measurements) across the various divisions of STR. These ‘beats’ are then scanned for the presence of tiger and other wildlife, helping identify promising camera-trap locations. Thereafter, small groups of department officials are given their own ‘beats’ to set-up camera traps over a 5-6 day period. After this, each team will then record the camera’s status, update the GPS coordinates of its exact location, ensure its proper functioning, and return consecutively over the following 4-5 days to evaluate its performance and download data that is time-stamped and geo-tagged. Common issues to look out for include lack of battery charge, memory card failure, theft, improper angle of the camera, or damage from an inquisitive elephant that might have tampered with it. After these routine checks, cameras are left alone for 25 days. I found it interesting to note that in STR, sampling occurs in two blocks. Each block is operational for 25 days, with 5-6 days given in between for cameras to be moved from one block to another. Therefore, the window of sampling approximately totals 60 days (e.g. 5-6 days for camera set-up and routine checks (per block), and a 25-day period of monitoring (per block)). Such timelines are driven by an assumption of closure. This assumption states that over the duration of the survey, the subject in question (i.e. the tiger’s population) must be demographically and geographically closed (i.e. no births/ deaths and no immigration/ emigration); helping the population survey to remain relatively unbiased. Typically, if sampling is completed in about 60 days (as per the above break-up), one can generally meet the closure assumption.

Each camera serves as a treasure trove; documenting the presence of numerous inhabitants and species; including other equally difficult-to-see creatures like the enigmatic black panther, or small cats; whose population and behavioural patterns are not as well documented or researched due to their rarity. After downloading data, counts can be corrected based on the probabilities of animals recorded, while accounting for those who remained undetected (indicating either complete absence or a ghostly stealth and natural prowess for avoiding detection). Images can also provide us with other vital insights that can inform the larger picture of tiger conservation. For example, ascertaining where firmly-held territorial boundaries are marked, distinguishing the birth of, and/ or presence of cubs, or developing an appreciation for the queer quirks of an individual tiger, or their preferences and fondness for revisiting a certain ‘beat’.